Yesterday was the start of a five-part series discussing the youth unemployment crisis. I spent a great deal of time explaining the background of the crisis and offered readers number of important links and statistics to better understand the situation. This discussion tied into a warning given by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The OECD is cautioning policy-makers that youth are at risk of becoming a "lost generation" if the current crisis is not dealt with appropriately. If you missed part one click here to be redirected. Today's installment will examine the ramifications of the youth unemployment crisis on the individual as well as society.

Individuals who are unable to fulfill these functions are more likely to be depressed and frustrated, and therefore more inclined to act irrationally by taking risks they would otherwise avoid. This behavior often includes violence, drug use, and alcohol abuse. The disillusionment brought about by unemployment can be seen in many low-income neighbourhoods where the risk-taking behavior is most clearly on display. According to Nasir "direct and indirect benefits of employment have been identified as protective factors from heavy involvement in these risk-taking behaviours." Clearly not everyone who is unemployed and living in a lower-income neighbourhood is involved in this behaivour, but evidence shows that those who are unemployed are more susceptible to being drawn into these activities.

Another impact of the youth unemployment crisis is the disconnect it can create in job seekers who are unable to find work. According to a study conducted by the Institute for Labor Market Policy Evaluation (IFAU) the experience of being unemployed may "diminish young people's feeling of attachment to the labour market". This detachment is exasperated when young, unemployed people seek each others company because the group may 'reduce the stigma' of unemployment; which would result in the youth be less inclined to look for work.

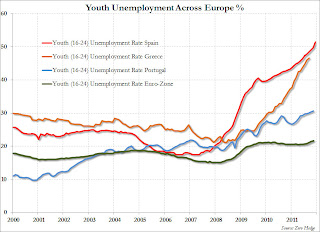

The Toronto Star posted an article today that addresses some of the social concerns when dealing with the crisis. Madhavi Acharya-Tom Yew, a business reporter for the Star, quoted experts as saying "the risks range from social unrest to mass migration to a wage gap that can persist for a decade, or even longer." An example of the unrest that the experts refer to can be found in Greece where, according to Charles Beach who is an economic professor at Queen's University, the unemployment rate of youth is 50 per cent. Yew continued to quote Beach in the article:

If youth aren't getting that labour market experience, that has a scarring effect which can last a long time. Multiply that by thousands of young people, and there are implications for the wider economy. In the economy as a whole, there's less skill that's built up. That will have a long-term negative impact on the collective knowledge base and GDP growth. Individuals who have lower income and not as many opportunities may delay marriage and starting a family. Many young people decide to go abroad to find jobs.These consequences are nothing new and have been studied extensively. Many studies support the claim that a delay in employment has a negative impact on future earnings. BBC News posted a story on their website in 2011 that addressed the future cost of youth unemployment. The journalists who wrote the story state, "a year of youth unemployment reduces earnings 10 years later by 6% and means that individuals spend an extra month unemployed every year up to their mid-30s." The article continues, "These penalties not only harm people's lives but cost governments and society at large a lot of money, both currently in terms of higher unemployment benefits and lost tax revenue and also well into the future through long-term reduced productivity and earnings, and more unemployment."

The ramifications of the youth unemployment crisis are staggering for individuals who are struggling to enter the workforce in order to begin their careers, and for society as a generation of workers are either unemployed or underemployed. While some political figures have been quick to blame the youth for not being willing to accept specific jobs or classified them as being unqualified, this is simply not the case. In fact many experts have stated that today's generation is more highly trained than any other generation preceding it. It's becoming more difficult to convince today's youth of the importance of a post-secondary education when most will graduate with a substantial debt and no job to show for it.

No comments:

Post a Comment